Varia: Pander's Ground Jay

5 October 2016 · Enno Ebels · 7097 × bekeken

490 Pander’s Ground Jay / Turkestaanse Steppegaai Podoces panderi, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan, 3 July 2015 (Enno B Ebels)

The four species of ground jay Podoces from Central and East Asia occupy a particular place within the Corvidae (crows and jays). They are mainly terrestrial and pale (buff) plumaged, whereas most crows and jays are dark coloured, arboreal and more aerial in behaviour. In shape, plumage and behaviour, ground jays are more reminiscent of typical desert species like Cream-colored Courser Cursorius cursor and Greater Hoopoe-Lark Alaemon alaudipes. The four species are Pleske’s Ground Jay P pleskei, which is (near-)endemic to Iran; Pander’s Ground Jay P panderi, which occurs in western Central Asia; Henderson’s Ground Jay P hendersoni, which occurs (only) in Mongolia; and Biddulph’s Ground Jay P biddulphi, which is endemic to north-western China. They have restricted and hardly overlapping ranges and are, therefore, quite a challenge to add to a birder’s list and even form a special quest for some birders (see, eg, Bakker 2011). In addition, they occur in barren and hot to very hot desert areas which may be difficult to reach and where birding can be arduous (Goodwin 1986, Madge & Burn 1994, del Hoyo et al 2009). Formerly, a fifth and much smaller species (the size and shape of a wheatear Oenanthe) was recognized, Hume’s Ground Jay, but this species is now considered to be a ‘terrestrial tit’ rather than a ground jay, and is currently known as Ground Tit Pseudopodoces humilis (Borecky 1978, Hope 1989, Londei 1998, Gebauer et al 2004, Johansson et al 2013).

The typical habitat of ground jays is barren ground with scattered scrubs. They need some vegetation for the seeds and small animals they feed on, as well as for shelter and nesting. Their long, curved and strong bills are adapted for digging and probing and they have obviously specialised to living on desert ground (see, eg, Londei 2004). Londei (2004) described that ground jays enhance their cryptic appearance by ‘expanding’ the scapular feathers and feathers of the ventral tracts to cover the conspicuous black and white feathers of the closed wing. To advertise their presence, birds simply reverse this procedure.

Ground jays are generally poorly studied; for instance, their conservation status is poorly known, although del Hoyo et al (2009) assume a general decrease in numbers owing to habitat degradation. Population assessments of ground jays have been mainly based on roadside counts. The attraction of ground jays to roads is probably of ancient origin, at least since the various routes of the Silk Road across Asia were established. Scully (1876) already noticed the habit of Henderson’s Ground Jays to come down to the path along which the horses had gone, to feed on the dung, probably to obtain both grains and beetles. He also reported on a local name of this species: ‘the Turki name is Kil yurgha, which has reference to the bird running in the trail of horses; it is also, though rarely, called Kum sagUzgliani, or ‘sand magpie’’ (cf Sharpe 1891). A preference for caravan paths was also reported for Henderson’s feeding on dung, garbage and dropped grains (Dementiev & Gladkov 1954), while Pleske’s Ground Jays have been observed in the early morning and late afternoon running in search of spilt grains on roads between villages (Hamedanian 1997, cf Londei 2011). The positive effects of roads on bird abundance may more easily be detected in deserts than in other habitats because birds may find important resources along roads that are scarce elsewhere in the desert, such as food and water aimed at human use (Londei 2000, 2011). As a result, roads may affect the abundance of animal populations and roadside counts may bias the regional status. Fahrig & Rytwinski (2009) reviewed 79 quantitative studies of the effects of roads on animal abundance across various taxa and concluded that the documented negative effects (mainly habitat loss and traffic mortality) outnumbered the documented positive effects (eg, increased resources and decreased predation), by a factor of five (cf Londei 2011). The authors, however, acknowledged that researchers may have purposely selected study species and situations in which they expected a negative effect, which may have biased their estimate. Li Zhong-qiu et al (2010) described an opposite example for ground-dwelling birds that benefit by roads in desolate regions.

Pander’s Ground Jay

Pander’s Ground Jay breeds locally in Kazakhstan and in large parts of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Two subspecies are recognized. Nominate P p panderi occurs rather commonly in suitable habitat in the Kyzyl Kum desert and Karakum desert in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and in very small numbers in neighbouring parts of Kazakhstan. P p ilensis has a restricted and isolated range in south-eastern Kazakhstan, south of lake Balkash, and is very rare; it has not been reported for several years, despite visits to the known area (Wassink & Oreel 2007, Wassink 2015; www.birds.kz). Ilensis is larger and darker than nominate panderi and the black spotting on the breast is larger (Madge & Burn 1994, Ayé et al 2012). Pander’s is named after Heinrich Christian von Pander (1794-1865), a German/Latvian geologist and palaeontologist; in 1820, he took part in a scientific expedition to Bukhara in Uzbekistan, close to Pander’s current breeding areas. Pander’s is closely related to Pleske’s Ground Jay, which occurs in Iran (and probably in bordering areas in Afghanistan and Pakistan; Goodwin 1986, Hamedanian 1997, Cowan 2000, Rasmussen & Anderton 2005). Both differ from the other two ground jay species in lacking black on the crown and in having relatively short uppertail-coverts, pale legs and a blackish breast patch.

491 Pander’s Ground Jay / Turkestaanse Steppegaai Podoces panderi, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan, 3 July 2015 (Enno B Ebels)

Pander’s Ground Jay is a bird of sandy desert with dunes and strong coverage of shrubs. It forages along sandy tracks, digging at animal droppings and searching at the base of bushes. It buries food in the sand to create food caches. It mainly eats seeds but becomes insectivorous in spring and summer, when prey items include beetles and small lizards (Madge & Burn 1994, Cowan 2008). The song is a clear ringing sound, delivered from bush tops, especially in early morning or evening. The species also utters chattering contact notes (Ayé et al 2012). Usually, birds are observed in pairs or family parties. There is no plumage difference between the sexes in adult plumage but young birds lack the black breast-patch and blackish lore and are more buffy (less grey) on the upperparts (Madge & Burn 1994).

The spherical nest is built in saxaul or Calligonum bushes at 0.15-2.5 m above the ground. Both partners build the nest for c two weeks from late February to late March. Eggs are laid from mid-March (or even late February) to late May. Females incubate the clutch of three to six eggs for 16-19 days, with food being provided by the male. Both parents feed the juveniles, which fledge when 18-20 days old. Fledglings are mostly recorded in early June to the first half of July but the first fledglings probably appear much earlier. Pairs commonly nest again after the loss of the first clutch (Madge & Burn 1994, Gavrilov & Gavrilov 2005, Cowan 2008; www.birds.kz).

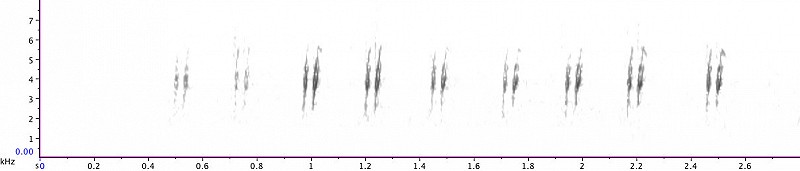

Figure 1 Pander’s Ground Jay / Turkestaanse Steppegaai Podoces panderi, chatter call, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan, 3 July 2015 (Enno B Ebels) [sound recording / geluidsopname]

Finding Pander’s Ground Jay

One of the best places to observe Pander’s Ground Jay is the Kyzyl Kum desert in north-western Uzbekistan (which extends across the border in eastern Turkmenistan). Birds can usually be found on both sides of the main road from Bukhara to Nukus, the best areas being between c 160 km and 180 km north-west of Bukhara (plate 492-493). Early morning is the best period, because later on the day the heat may become too much and traffic increases on the road. In early morning, birds can be seen foraging close to the road or even on the asphalt. On 3 July 2015, during a private birding and culture trip to Uzbekistan – following a stretch of the former Silk Road – I managed to observe c 10 birds within a stretch of c 20 km, including a group of at least three, among which at least one young bird (plate 490-491 and 496-497). I managed to make some recordings of the chattering double note (figure 1); this call differs from the only call present in the online library Xeno-canto (www.xeno-canto.org/148565), which consists of quickly repeated single notes. The behaviour to forage close to the road is not without risk, because birds may be hit by passing cars or blown onto the road by the winds created by passing lorries. Plate 494-495 show a wounded young that had apparently just been hit, being attended by its parent.

492-493 Habitat of Pander’s Ground Jay Podoces panderi along road from Bukhara to Nukus, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan, 3 July 2015 (Enno B Ebels)

494-495 Pander’s Ground Jays / Turkestaanse Steppegaaien Podoces panderi, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan, 3 July 2015 (Enno B Ebels). Moribund young, apparently just hit by car, attended by parent.

496-497 Pander’s Ground Jay / Turkestaanse Steppegaai Podoces panderi, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan, 3 July 2015 (Enno B Ebels). Plate 497 shows young bird.

How to get there and when to go?

Bukhara can be reached directly by airplane from Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, and also from Moscow, Russia. International flights go to Tashkent mainly from Istanbul, Turkey, or Moscow. Overland, Bukhara can be reached by train or car from Tashkent (distance almost 600 km, a full day’s drive by car). The regular train ride takes 6 h and 40 min; the first stretch (Tashkent to Samarkand, just over 300 km) can also be covered by high-speed train (the ‘Afrosiyob’) in little over 2 h. Private car rental is complicated in Uzbekistan but hiring a car with a driver for one or more days is no problem. The ground jays can probably be observed all-year round but winters are cold in Uzbekistan (with temperatures around freezing point and often below) and it may be hard to find birds then. In spring and autumn, temperatures are better for birding, whereas in mid-summer, temperatures can easily reach 45°C or more around mid-day.

Other interesting bird species

During my visit to the Kyzyl Kum desert, I observed two males Saxaul Sparrow P ammodendri (an uncommon species in Uzbekistan) near a drinking spot where several Indian Sparrows P (domesticus) indicus and Desert Finches Rhodopechys obsoletus were present. While observing the ground jays, Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia nana and Scrub Warbler Scotocerca inquieta platyura were found.

Zarudnyi’s Sparrow P zarudnyi could potentially be another target species for birders in this area (especially since its upgrading to species level; Kirwan et al 2009) but has not been observed in Uzbekistan in recent years (last report in 2007; Kirwan et al 2009) despite having been searched for regularly by local ornithologists, so the chances to encounter one appear to be very low. From Bukhara, Repetek nature reserve in Turkmenistan, probably the most reliable place to see Zarudnyi’s Sparrow (cf Kirwan et al 2009), is ‘only’ c 170 km by car. If one would arrange a visa in advance and could change taxis at the border, a visit to Repetek can be an option from Uzbekistan. Note, however, that the species has also become hard to find in Repetek in recent decades (Kirwan et al 2009).

Acknowledgements

Arnoud van den Berg and Magnus Robb kindly helped to prepare the sonagram.

Enno B Ebels, Joseph Haydnlaan 4, 3533 AE Utrecht, Netherlands (ebels@wxs.nl)

References

Ayé, R, Schweizer, M & Roth, T 2012. Birds of Central Asia. London.

Bakker, T W M 2011. Expedities van het Groot Grondgaaien Genootschap in Centraal-Azië. Vogeljaar 59: 275-281.

Borecky, S R 1978. Evidence for the removal of Pseudopodoces humilis from the Corvidae. Bull Br Ornithol Club 98: 36-37.

Cowan, P J 1996. Desert birds of the Caspio-Central Asian desert. Global Ecol Biogeogr Letters 5: 18-22.

Cowan, P J 2000. The desert birds of south-west Asia. Sandgrouse 22: 104-108.

Cowan, P J 2008. Photospot: Pander’s Ground Jay Podoces panderi. Sandgrouse 30: 204-205.

Dementiev, G P & Gladkov, N A 1969. The birds of the Soviet Union 2. [English translation of Ptitsy Sovietskogo Soyuza.] Jerusalem.

Fahrig, L & Rytwinski, T 2009. Effects of roads on animal abundance: an empirical review and synthesis. Ecol Soc 14: article 21. Website: www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art21.

Gavrilov, E I & Gavrilov, A E 2005. The birds of Kazakhstan. Almaty.

Gebauer, A, Axel, J J, Kaiser, M & Eck, S 2004. Chemistry of the uropygial gland secretion of Hume’s ground jay Pseudopodoces humilis and its taxonomic implications. J Ornithol 145: 352-355.

Goodwin, D 1986. Crows of the world. Second edition. London.

Hamedanian, A 1997. Observations of Pleske’s Ground Jay Podoces pleskei in central Iran. Sandgrouse 19: 88-91.

Hope, S 1989. Phylogeny of the avian family Corvidae. New York.

del Hoyo, J, Elliott, A & Christie, D A (editors) 2009. Handbook of the birds of the world 14. Barcelona.

Johansson, U S, Ekman, J, Bowie, R C K, Halvarsson, P, Ohlson, J I, Price, T D & Ericson, P G P 2013. A complete multilocus species phylogeny of the tits and chickadees (Aves: Paridae). Molec Phylogen Evol 69: 852-860.

Kirwan, G M, Schweizer, M, Ayé, R & Grieve, A 2009. Taxonomy, identification and status of Desert Sparrows. Dutch Birding 31: 139-158.

Li Zhong-qiu, Ge Chen, Li Jing, Li Yan-kuo, Xu Ai-chun, Zhou Ke-xin & Xue Da-yuan 2010. Ground-dwelling birds near the Qinghai-Tibet highway and railway. Transportation Res Part D: Transport Environm 15: 525-528.

Londei, T 1998. Observations on Hume’s Groundpecker Pseudopodoces humilis. Forktail 14: 74-75.

Londei, T 2000. Observations on Henderson’s Ground Jay Podoces hendersoni in Xinjiang, China. Bull Br Ornithol Cl 120: 209-212.

Londei, T 2004. Ground jays expand plumage to make themselves less conspicuous. Ibis 146: 158-160.

Londei, T 2011. Podoces ground-jays and roads: observations from the Taklimakan Desert, China. Forktail 27: 109-111.

Madge, S & Burn, H 1994. Crows and jays: a guide to the crows, jays and magpies of the world. London.

Rasmussen, P C & Anderton, J C 2005. Birds of South Asia: the Ripley guide. Volume 2: Attributes and status. Barcelona.

Scully, J 1876. A contribution to the ornithology of Eastern Turkestan. Stray Feathers 4: 41-205.

Sharpe, R B 1891. Aves. In: Scientific results of the second Yarkand Mission; based on the collections and notes of the late Ferdinand Stoliczka, PhD. London.

Wassink, A 2015. The new birds of Kazakhstan. De Cocksdorp.

Wassink, A & Oreel, G J 2007. The birds of Kazakhstan. De Cocksdorp.

Published in the journal Dutch Birding volume 38 (2016) no 5 page 317-321 / Gepubliceerd in het tijdschrift Dutch Birding jaargang 38 (2016) nr 5 pagina 317-321